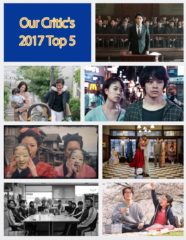

ROUNDUP: Our Critic’s Top 5 of 2017

2017 has been a lackluster year for Japanese cinema, considering how eventful 2016 was: no resurgence of Godzilla (let’s forget about the anime version), no Makoto Shinkai, and no rising talent winning awards at Cannes. Having said that, although they were fewer in number, there were some truly wonderful films released, especially by auteurs and established filmmakers who made comebacks after struggling in their careers.

Here is my Top 5 (not 10) list of theatrically-released Japanese films of 2017, and several honorable mentions.

5: Hanagatami

Legendary filmmaker Nobuhiko Obayashi was informed of his stage-four cancer and told he had only 6 months to live just before the production of his latest feature, Hanagatami. However, he managed to complete the film, and it turned out to be a masterpiece. Based on Kazuo Dan’s novella of the same name, the 169-minute-long Hanagatami is a tour-de-force achievement about complex love relationships among youths before World War II. The visionary director infuses the film with idiosyncratic Obayashi style: exaggeration, rhythmical editing, color extravaganza, repetitions of key moments, and naked women. As a result, Hanagatami is a camp anti-war movie that is capable of laughing at masculine power and militaristic ideology. Obayashi’s imagination has not aged at all since his debut feature House in 1977, and it certainly should continue for his next project, already announced.

4: Suffering of Ninko

Suffering of Ninko is no perfect movie. But it is the kind of film that has such remarkable creative energy, you can easily forget its flaws. Norihiro Niwatsukino’s debut feature is an erotic, hilarious jidaigeki (period piece) that tells of the religious struggle of a Buddhist monk who turns out to be sexually irresistible to many women. Niwatsukino depicts the protagonist’s sinful sexual fantasies through a number of alluring animations, full of rich aesthetics with moving Japanese-style paintings and grandiose music, rhythmically edited with images of male fantasies that accelerate carnal desire. Suffering of Ninko is the most WTF movie of the year, and that makes Niwatsukino the most inspiring newcomer.

3: The Tokyo Night Sky is Always the Densest Shade of Blue

Yuya Ishii is one of those filmmakers who became a successful independent filmmaker and then sold his soul to commercialism. Many who loved Sawako Decides (2010) got disappointed with what came after, The Great Passage (2013) and The Vancouver Asahi (2014). In 2017, however, Ishii made a pleasant and long-awaited comeback with the year's weirdest title, The Tokyo Night Sky is Always the Densest Shade of Blue, a poetic love story between two loners in the capital. Depicting Tokyo as the loneliest planet has become almost cliché, but Ishii’s free and visual approach successfully conveys a sense of isolation and loss of hope. Newcomer actress Shizuka Ishibashi especially shines as a nurse who moonlights as a hostess at night, and she promises to be the next Sakura Ando or Fumi Nikaido.

2: Dear Etranger

The family drama in Japanese cinema is a genre that is often criticized for its conservatism and traditionalism. However, Dear Etranger approaches its subject in an honest manner that uncovers the harsh reality. Following last year’s intriguing Night’s Tightrope, Yukiko Mishima creates another masterpiece that unveils mankind's hatred and mistrust, realistically presenting family conflicts that are the result of a wife’s pregnancy. Tadanobu Asano passionately plays a humanistic husband who attempts to make everything work between his pregnant wife, ex-wife, biological and non-biological children. Dear Etranger presents contemporary family conflicts as something unresolvable, but at the same time, shows characters finding ways to make it all work, at least for a while. In a country where people and the system itself dislikes children, Mishima may not believe in the family system anymore, but she certainly believes in people who can be responsible for own children and welcome the unborn.

1: The Third Murder

Japanese auteur Hirokazu Kore-eda seemed to be stuck in the same-old family genre and manga adaptations in recent years, but he used to ask lots of difficult questions. In his latest feature, The Third Murder, Kore-eda dives into the new territory of the mystery genre and courtroom drama, to ask unanswerable questions about truth and lies. In a gripping narrative about a lawyer representing a killer who keeps changing his story about what actually happened, the truth is distorted by characters just to create a Rashomon effect. The acting battles between genius actors Koji Yakusho and Masaharu Fukuyama drive the most powerful sequences in the film. In a prison visitation room, especially, the faces of the lawyer and the killer are superimposed as reflections on the glass between them, threatening the lawyer’s status as the interrogator. Through such alluring cinematography and the exploration of new genres, Kore-eda revealed hidden possibilities as a filmmaker, more than just the family guy, and reestablished his status as the leading filmmaker in Japan.

Honorable Mention: Close-Knit

Naoko Ogigami, a female director who is known for “iyashi-kei” (emotional healing) films, became sick of this label and took a different career path by making Close-Knit, a charming family drama with a transgender mother. Awarded in international film festivals galore, Ogigami’s latest has been the most popular title in her filmography, for its depiction of a queer family in a warm and optimistic manner. Significantly, Close-Knit marks the first Japanese mainstream film with a transgender protagonist. She is played by Toma Ikuta, a Johnny’s idol who can melt your heart. The film received some legitimate backlash because of this (Isn’t Ikuta too beautiful to be true? Doesn’t this depiction of a perfect mother only strengthen traditional gender roles?), but you have to start an argument somewhere, and Ogigami surely started it.

Naoko Ogigami, a female director who is known for “iyashi-kei” (emotional healing) films, became sick of this label and took a different career path by making Close-Knit, a charming family drama with a transgender mother. Awarded in international film festivals galore, Ogigami’s latest has been the most popular title in her filmography, for its depiction of a queer family in a warm and optimistic manner. Significantly, Close-Knit marks the first Japanese mainstream film with a transgender protagonist. She is played by Toma Ikuta, a Johnny’s idol who can melt your heart. The film received some legitimate backlash because of this (Isn’t Ikuta too beautiful to be true? Doesn’t this depiction of a perfect mother only strengthen traditional gender roles?), but you have to start an argument somewhere, and Ogigami surely started it.

Honorable Mention: Poolsideman

No contemporary Japanese filmmakers are as audacious as the Watanabe Brothers. However, precisely because of their politically-charged themes, minimalistic style and the lowest budgets imaginable, it is hard to figure out how they have managed to get theatrical releases for their films. But somehow they have, and this year they unspooled not just one, but two, new films: 7Days and Poolsideman. Unlike the ever-controversial 7Days, Poolsideman is the Watanabes’ masterpiece, and won them the Japanese Cinema Splash Best Picture Prize at the 29th Tokyo International Film Festival in 2016. With astonishing black-and-white cinematography, the film delves into the psychology of a reticent worker whose only interest seems to lie in terrorism. Poolsideman uncovers how universal concerns are relevant to Japanese people, even though they pretend that everything is okay on this insular island.

By Kenta Kato

Kenta Kato is a Tokyo-based writer, film critic and festival programmer, currently working on his PhD in Film at Waseda University.